Gilpin Court is Richmond's largest and oldest public housing project. It was built adjacent to I-95, a construction project that, ironically, demolished many of the original houses in the area.

A statue of Robert E. Lee, a famous Confederate general, sits in a prominent position astride a traffic circle near downtown. For many people, the Confederacy represented a desire to retain slavery.

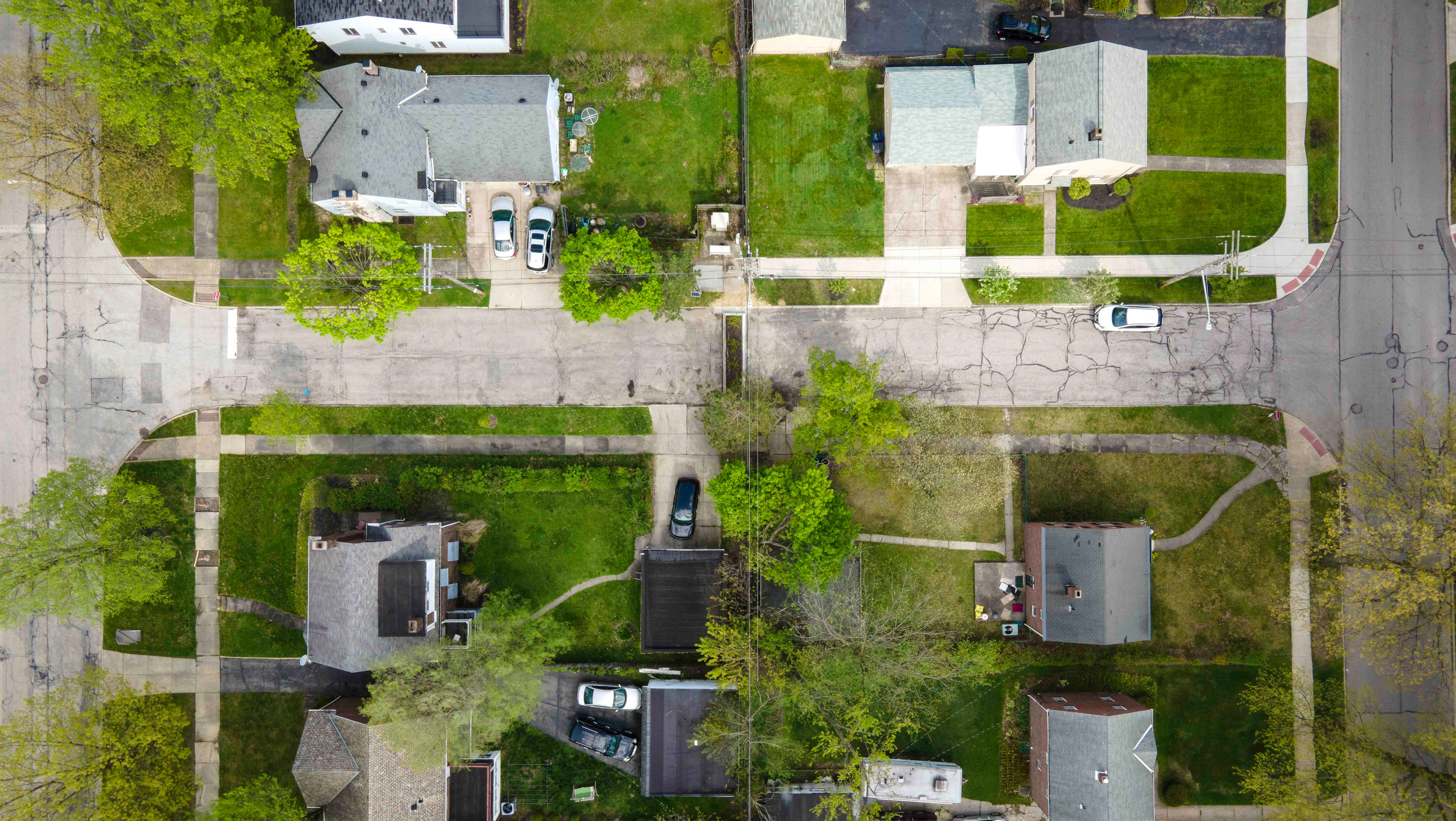

Looking south from the northern side of I-95, Jackson Ward is anemic, empty, and green.

One small victory was the Sixth Mount Zion Baptist church, a historic site of worship built in 1884, which had the misfortune to be located directly in the path of the interstate. With the bulldozers looming, a loud and furious resistance from community members prevented construction proceeding as planned. The church was permitted to stand, and the entire interstate was re-engineered to bend around it – one of the few symbols of resistance still visible.

This statue of Robert E. Lee was covered in graffiti after the 2020 protests against the murder of George Floyd. In 2022 it was finally removed and the plinth dismantled.